The business group, Business Roundtable issued a press release on Monday, August 19, 2019, saying they were redefining the purposes of a corporation to promote an economy that serves all Americans.

Business Roundtable, from their website: “is an association of chief executive officers of America’s leading companies working to promote a thriving U.S. economy and expanded opportunity for all Americans through sound public policy…. Business Roundtable exclusively represents chief executive officers (CEOs) of America’s leading companies. These CEO members lead companies with more than 15 million employees and more than $7 trillion in annual revenues.”

Their full statement is: here. I encourage you to read it first and make your own determination. I first came about it on a linkedin post by my friend Ben Narodick. Ben wasn’t a fan, and I can’t really say I am either.

This blog is focused on employees and their compensation, which was addressed in the Roundtable’s press release. The second of their five commitments in the letter:

“Investing in our employees. This starts with compensating them fairly and providing important benefits….” – Business Roundtable.

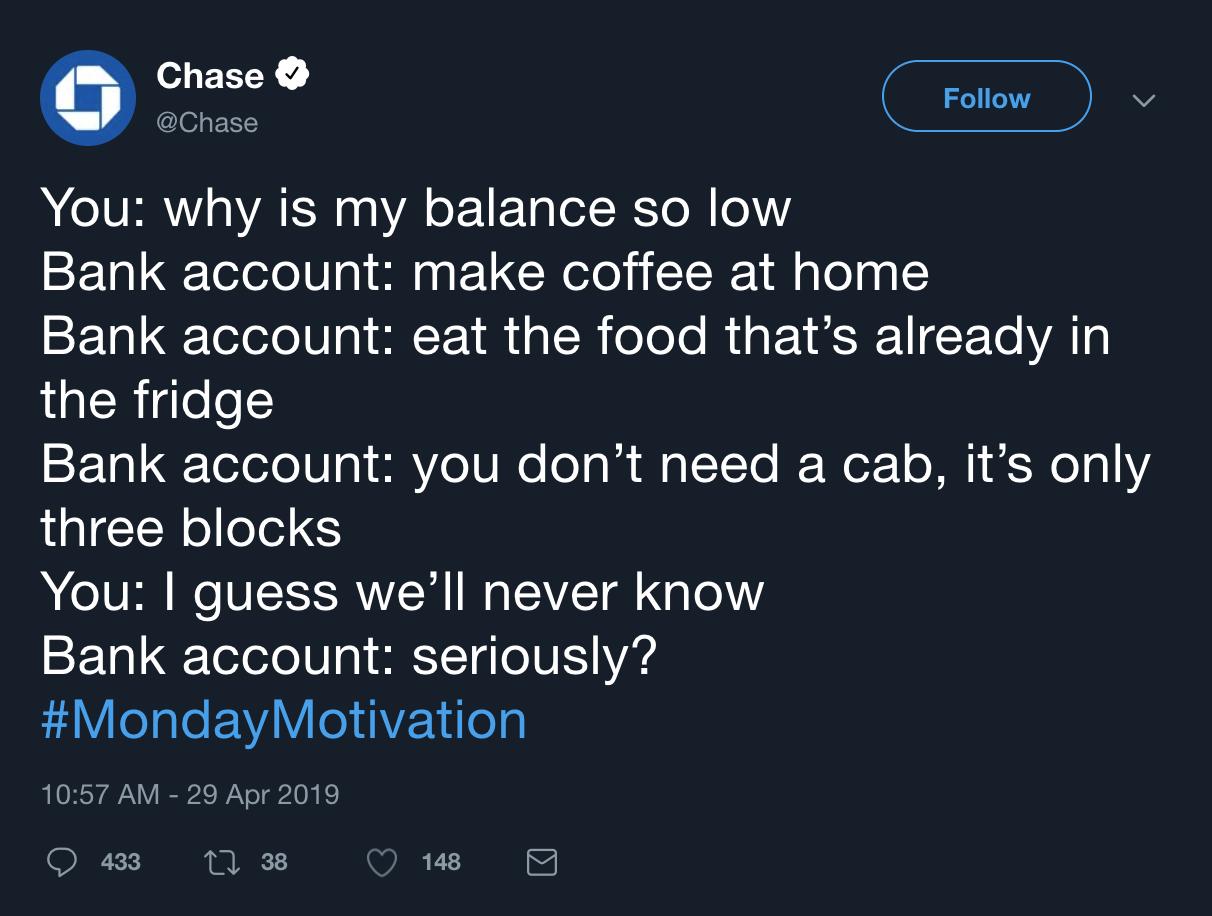

I don’t think that’s really saying a whole lot. Would they instead have said they were going to dis-invest from their employees? Compensate them unfairly? Take away benefits? Words matter, and as Ben pointed out, they’re really not using meaningful words. This is how I think it could have been more meaningful:

“Investing in our employees. This starts with compensating them MORE and providing important benefits, INCLUDING HEALTH INSURANCE WITH REASONABLE PREMIUMS AND DEDUCTIBLES, RETIREMENT, AND PAID TIME OFF.” – Anxious AF

But they didn’t say that – so it’s near impossible to actually measure whether or not the members of the Business Roundtable are actually improving their behavior in the way they want inferred.

181 CEOs “signed” the new Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation. And you know what I can add to this conversation? Spending time looking at financial statements. So this may be a running post series, but here some compensation details about the first five signatories.

NUMBER ONE: Kevin J. Wheeler. President and CEO of the A.O. Smith Corporation. From the company’s 2019 10K proxy filing. In 2018, Mr. Wheeler’s total compensation was $ 3,872,974 . That’s 200 times their median salary employee of just over $19K/year (or less than $10/hour for full-time work). Side note, Mr. Wheeler gets a $40,000 “allowance” (twice their median salary). He was also not the highest paid employee at AO. That was Executive Chairman Ajita G. Rajendra, who made $6,790,412.

NUMBER TWO: Miles D. White. Chairman and CEO of Abbott. Per their proxy filing from March 2019, Mr. White made over $24M in 2018. Abbott reports its median employee income as just over $80,000; bringing the CEO pay ratio to 301 to 1.

NUMBER THREE: Julie Sweet, CEO Designee of Accenture. Ms. Sweet made almost $5.9 Million in 2018, as the North American CEO. Pierre Nanterme, the organization’s CEO made over $22M in 2018. Per their proxy, Accenture’s median employee made just over $40,000 in 2018; giving them a CEO pay ratio of 555:1.

NUMBER FOUR: Carlos Rodriguez, President and CEO of ADP. $12M in 2018. Median Employee: just under $60,000. Ratio: 211:1. Here’s their proxy.

AND NUMBER FIVE: Michael Burke, Chairman and CEO of Aecom. $15.6Million in 2018. Median employee made $78,516. Ratio: 200:1. Here’s that proxy.

For those of you playing at home, you can refer back to my first post, wherein I arrived at a high x80 ratio that one might expect from the highest paid executive at any company. All of these companies are well above that – at least double.

In summary: the worst offender so far: ACCENTURE (x555). The “best” (?) offender? I’ll skip AO Smith, given their particularly low median income, and go with Aecom (x200).

I don’t know about you, but I can’t WAIT to see what the rest of the list brings.

Pay your people and put your money where your mouth is,

The Anxious Amateur Economist